Fostering Change

Others, Growth , RelationshipsContributed by: Chalmers Center

By the Chalmers Center

Adapted from Chalmers online training Helping without Hurting in Benevolence Ministry.

The ultimate goal of poverty alleviation and development is restoration of people to all that God has created them to be—priests and rulers who proclaim His glory to the world and call others to worship Him. A nearer-term goal is change. We long to see transformation in the lives of those we serve, both in their material well-being and their spiritual lives. The role of a local church, ministry organization, or individual in this process is to be a facilitator, not an agent of change. Change is God’s job.

As we have opportunities to walk with people, however, we participate in mutual transformation—we expect God to change us even as we hope for change in the lives of others. Most poverty alleviation requires a long-term process, moving both materially poor and materially non poor toward restoration in four key relationships: with God, self, others, and the rest of creation. This process takes time, and change is difficult for most people. Expect to keep learning and re-learning along the way.

How Do People Change?

Even though transformation is ultimately the work of the Holy Spirit, He can and does work in and through individuals, churches, and other organizations to bring about change in people’s lives. Within that understanding, researchers and practitioners have observed some fairly regular patterns in the way that human beings experience change or adopt new ideas, patterns that can be used to encourage the kind of changes that are at the core of the development process.

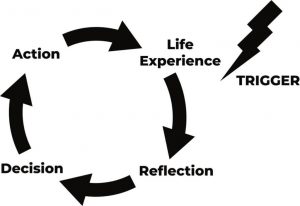

All change starts from a context—who people are, their life experiences, their set ways of understanding reality, etc. For people to change, they have to be willing to look at this context, to reflect upon it and ask some hard questions. Out of that, they may begin to recognize that there are aspects of their life that are not satisfying, painful, or destructive. This process of reflection can be done in dialogue and community, but hopefully leads to the internal motivation to make a decision for change. Someone may recognize, for example, that they are tired of not being able to pay their bills every month and decide to commit to taking action to earn more money, spend less, budget better, or pursue some other solution.

This cycle of 1) starting from life experience, 2) reflecting on it, 3) making a decision for change, and 4) acting on those decisions needs to repeat itself over and over in different areas of someone’s life if they are going to continue to make positive changes. This cycle may take a short time for some issues and extended periods of time for others—years or even decades. It can be observed in changes experienced by whole communities or people groups as well.

Triggers for Change

What causes people to be willing to begin this process of moving beyond their status quo? The change cycle usually begins when something triggers the individual or group to begin the process of reflecting on their experience. A central component of poverty alleviation can be looking for opportunities to foster triggers for positive change within the context of healthy, trusting relationships.

Three common triggers for change for individuals or groups have been identified, and the role of helpers in each scenario is different.

- A recent crisis event. This could be a widespread event—like a natural disaster or economic crash—or individualized—like a car accident or medical emergency. It could be external, like the examples above, or internal—such as experiencing a mental health collapse, family strife, or committing a crime. The role of a helper in this situation may simply be to be present and committed to the relationship, and then to ask questions that help someone examine themselves and to provide encouragement when they start to consider making positive changes.

- The status quo becoming unbearable. Sometimes no specific event sparks reflection, but rather the slow, steady recognition that the way things are is not working. This could be something like seeing how a cycle of taking out credit card debt or payday loans to pay off existing debt is digging a hole too deep to get out of, or continually having trouble getting a decent job leading someone to wonder what it would take to finish their GED or go back to school. For helpers in this situation, the role is more engaged. Seeking to help requires us to know a person’s history and personality well enough to ask more pointed questions to help them reflect on their life. It could include advocating for someone to seek justice for an oppressive situation beyond their control. Depending on the relationship, it may also mean stopping handouts or gently removing the “buffers” that have been shielding someone from feeling the full effects of their life choices.

- Encountering a new way of doing or seeing things. This could be any sort of training or ministry program that presents an opportunity to “try something new” that is relevant to someone’s situation and that can be acted on quickly. Here, the role of a helper is often to bring forward these ideas and walk with people across time as they consider them. Most economic development interventions—like jobs training, financial education, savings groups, etc.—center on introducing new possibilities for positive change to individuals and communities. Within an asset-based, participatory approach, even asking questions like, “What gifts and abilities do you have?” or “What are your dreams?” can be simple but powerful tools to prompt openness to change.

Patience and Presence (1)

Note that even if one of these change triggers results in some reflection, it is not at all automatic that the rest of the cycle will result in major actions or significant changes or even that the cycle will proceed at all. Indeed, a host of obstacles can get in the way of significant change. A major part of the process is coming alongside materially poor individuals or groups to help them remove obstacles to change that they are incapable of removing on their own. One of the most significant obstacles to change is a lack of supportive people. We all do better when we have people cheering us on, supporting us through prayer, offering a listening ear, and lending a helping hand when we need it. Unfortunately, many times when people start to pursue positive change, the people around them feel threatened or jealous, and they actually start to fight against the person’s efforts to change.

That said, individuals and communities have varying degrees of receptivity to change. We are called to love people in all degrees of receptivity, but the way that we love them will look different because their situations and attitudes are different. As described in trigger #2 above, a loving, faithful response to someone who simply has no desire to make any changes in their lives might be to withhold some material assistance to allow them to feel the burden of their situation. A loving, faithful response to someone who is demonstrating action steps toward growth might look much more generous. A response to those in between those two extremes might be to help someone see their own role in their situation or help them overcome external obstacles to change. In every case, we should remember that the Bible does not command mindless “generosity,” but rather the use of wisdom and prudence that keeps the end goal in mind: restoration of people to who they were created to be. Any action that undermines this grand work of God in the lives of the poor is contrary to God’s purposes—even if it is well-intended.

It is useful to have tools that measure and reveal people’s receptivity to change, especially to uncover two key things: 1) Does the individual or group understand their part—whether large or small—in causing themselves to be in this situation? Poverty is complex, resulting from many causes, so it is crucial that people identify any portion of the problem that is of their own making so that they can begin to address these issues. 2) Does the individual or group understand that they have the responsibility to take some actions to improve their situation, even if not all aspects of the situation are within their power to change? An important caveat to this would be if an individual is struggling with mental health issues such that they do not have the capacity to make responsible choices on their own.

Remember, it is not only the materially poor who need to change. We all need to change, because we are all poor in different ways. Many materially well-off churches and ministries need to experience their own triggers of change, triggers that can propel them into a far more transformative and empowering approaches to ministry.

For more on this topic, see chapters 10 and 11 of When Helping Hurts or Helping without Hurting in Benevolence Ministry.